In the 1930s the Austrian psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich (1897–1957) came up with his concept of “character armour” (Charakterpanzer) to explain how we defend ourselves from emotional pain. Character armour was a physical manifestation—like muscle tension, locked posture, repetitive patterns of speech and behaviour—of an emotional blockage. He believed for instance that Freud’s jaw cancer was not caused by his smoking but by his biting down on his impulses. Reich would attempt to work through psychic tensions like these with massage, and to retrieve with his hands repressed memories of childhood trauma. If successful, waves of pleasure would flow through his patients’ bodies: he called this the “orgasm reflex.”

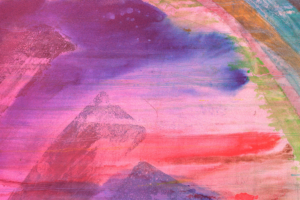

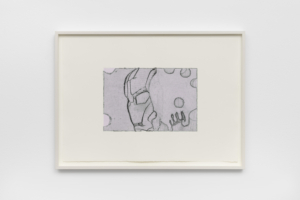

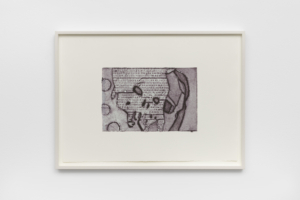

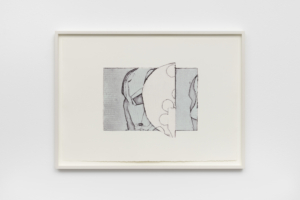

Kyle Thurman’s ongoing series of Dream Police paintings began when he stumbled across a network of hobbyists that spend their spare time designing and customizing fantasy body armour for Marvel superheroes and other heroic characters using 3D modeling software. They 3D-print and airbrush it, and film themselves wearing it. They have file-sharing websites where they upload their designs with the community so others can download and build them. It is very collective and free. For this exhibition, Thurman has painted six of these files across four paintings: all variations on the Iron Man suit, including an Iron Man-Captain America hybrid; this is the figure with a star on their chest. These are paintings of popular online folk culture.

When Stan Lee thought up Iron Man in the 1960s, his intention was to write a character Marvel’s readers would very much dislike: a billionaire philanthropist arms dealer, modeled on Howard Hughes, with enough money to make his own cyborg bodysuit. But Iron Man quickly became a massive success and is even more successful today. Many identify with him, perhaps because he is a mythical hero of a different sort: he doesn’t have magical superhuman powers but is instead transformed by technology. The hobbyist-armourists’ love of costume suggests a desire for power and control, and protection from violent, bloodthirsty times—but also a liberatory project of projective imaginary pleasure and self-transformation through virtuality. They are not alone: we are all wearing fantasy character armour now. The internet allows us to live behind masks, to sculpt our identities like clay and to imagine ourselves as different beings, and an increasingly large share of our selves is now dissipated over its servers.

Each Dream Police painting has a subtitle in parentheses: my stomach … your jaw. When there are two figures: our lungs … our breast with eclipse. These iron bodies join everybody, you and I, in a space we can dream and have nightmares together inside, a shared fluorescent consciousness. These paintings are anti-figurative because they are representations of only a shell, that conjure a figure without showing one. They leave it to our imagination. These are not representations of a specific figure but of a stock character or mythical type: the Dream Police. This symbolist form that gives off a charge. Who are these Dream Police? Do they legislate what you can and cannot dream? Do they allow you to confess, to be free of your sins? Do you dream of becoming one?

The show’s title “Accumulator” references Reich’s invention of the orgone accumulator. He believed in a universal life force called “orgone” and, after emigrating to the United States in 1939, founded his Orgone Institute in 1942 on an estate in Rangeley, Maine. His accumulator was a metal-lined box for collecting orgone energy from people and the environment. Thurman’s dripping neon armours, likewise, might also be understood as both redemptive confessional spaces and orgasmic transmission boxes, for gathering the amazing amounts of human energy that 21st-century technology has accumulated for and extracted from all of us.

Dean Kissick