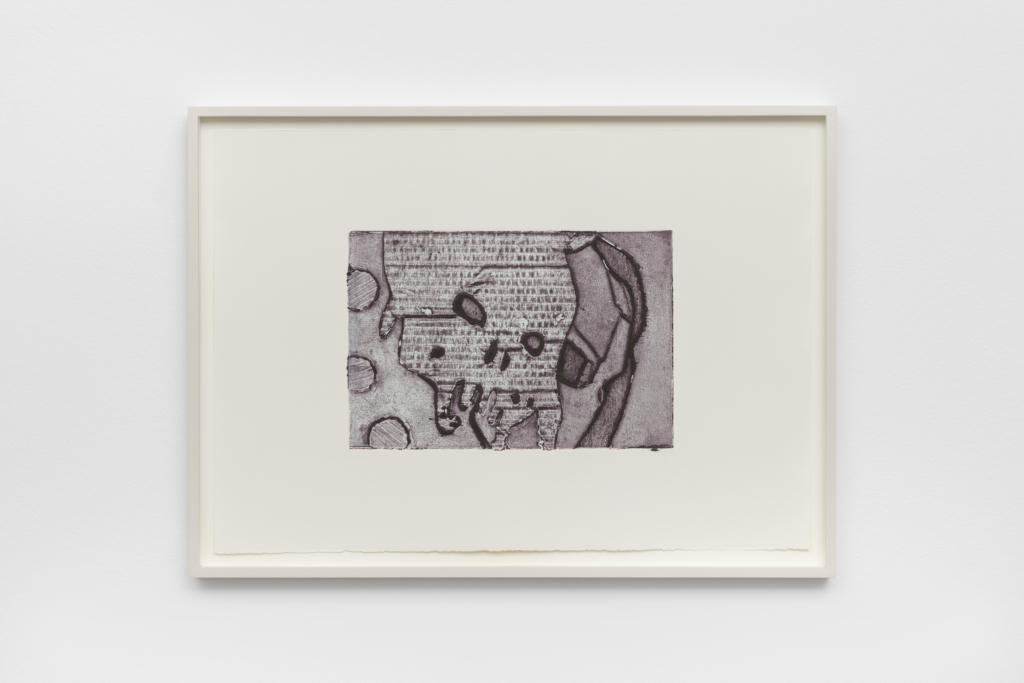

[…] Many of Thurman’s Dream Police paintings have a slightly weathered, fuzzy feeling to them. Dreams and drawn ideas diminishing into impermanence. The works are fabricated by mixing dispersion pigment, gouache, oil, and watercolor on jumbo wood panels. The application of water-soluble pigments onto a wooden surface nods at thwarted attempts to recall night wanderings. Dreaming is the kind of repeated activity that cultivates language’s and the body’s inwardness, vulnerability, and uncertainty. A dream’s eddying indeterminacy is a reminder that tools like language and the body regularly fail us.

Each Dream Police work measures 48 inches by 72 inches (122 centimeters by 183 centimeters) and is outlined by a unique artist’s frame. The work’s dimensions evince a quality at once celebratory and familiar. Bigger is better—these are some of Thurman’s largest works as of late—but, its specific dimensions also pay homage to at-home movie projectors, which proliferated during the recent COVID-related lockdowns. Projectors are now a staple household appliance, both affordable and able to cast higher quality images. Peek into your neighbor’s apartment window and you might just catch a cast of armored superheroes, minions, and villains on walls in roughly the same dimensions as these works.

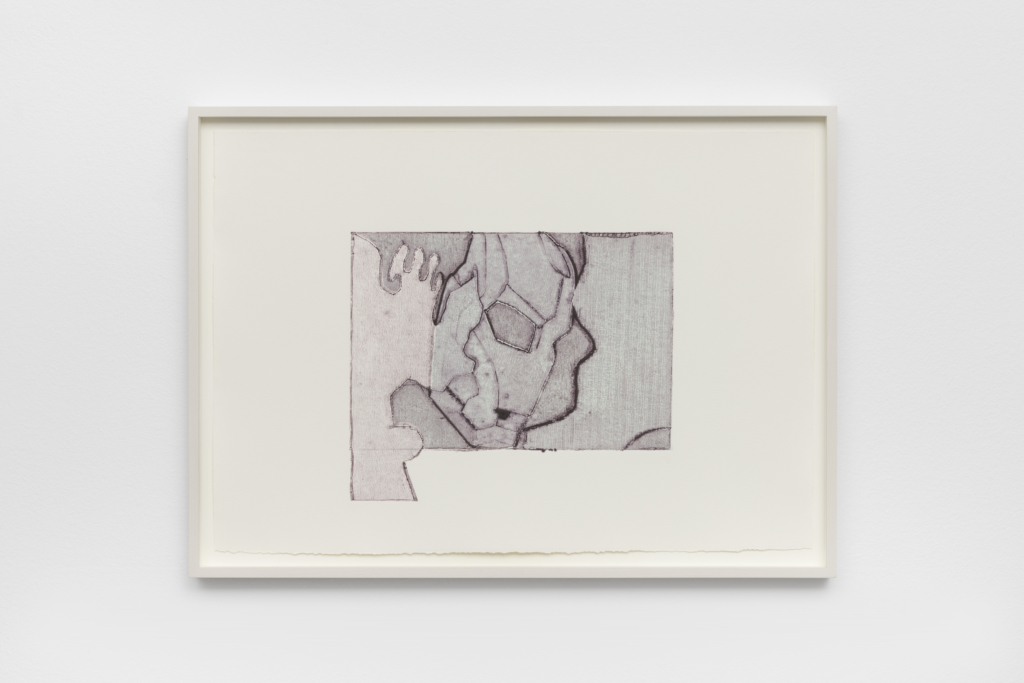

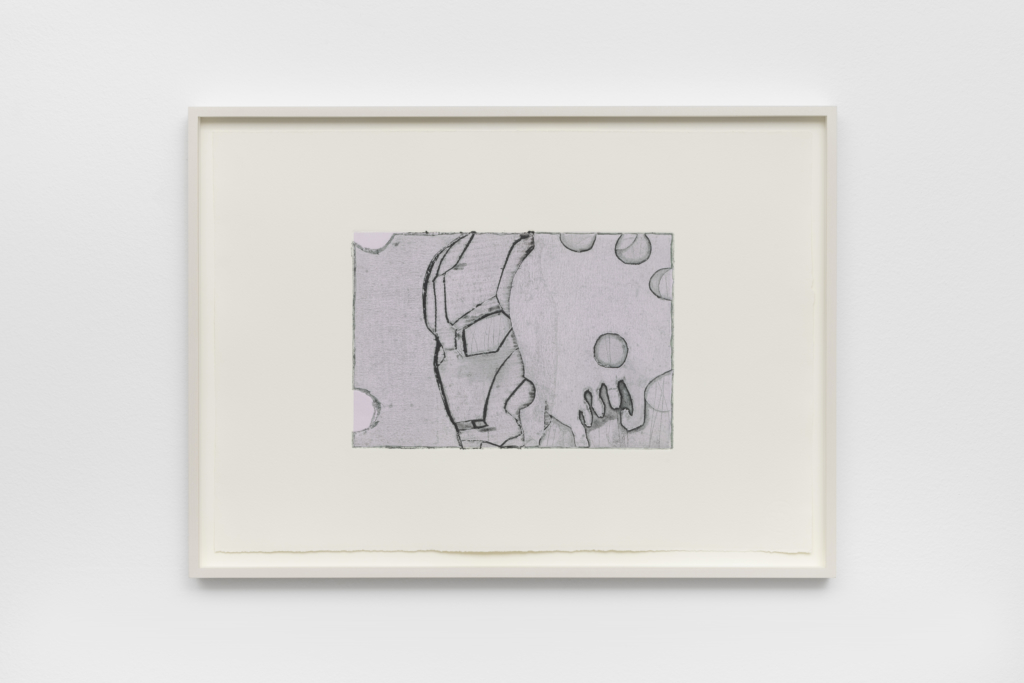

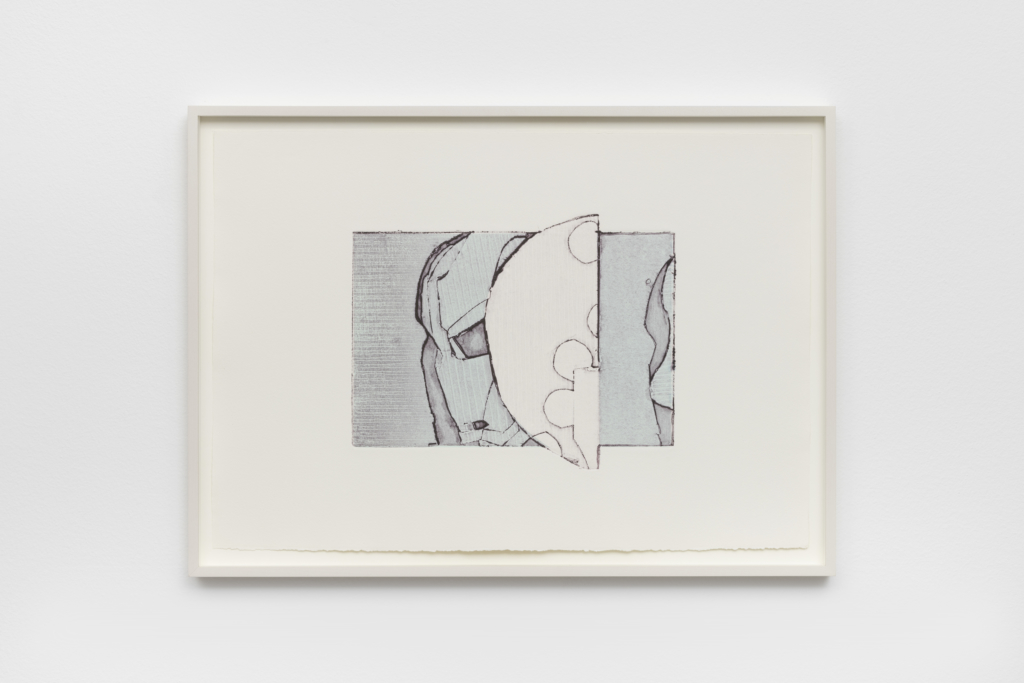

Beyond the artist’s drive to conjure up characters of a certain size, he’s also motivated by the abundance of body armor that clouds our off-white bedroom walls. Figments of body armor from the Marvel Cinematic Universe, like Tony Stark’s Iron Man suit, Captain America’s electromagnetic exoskeleton, and Thor’s battle armor appear in several works. In other works, there’s perfunctory references to the extraterrestrial-plated robot foreigners, the Autobots and the Decepticons, from Michael Bay’s Transformers series. These giants appear closer to the picture plane as if a single-player soldier in a story mode video game locked in immortal combat.

Thurman has something to say about these cast of soldier-like characters: “In the earlier months of the pandemic, like most people, I was spending a lot of time on social media. Instagram, TikTok… A fandom of people who 3D print and customize their own fantasy body armor flooded my algorithms. Marvel superheroes, most frequently Iron Man, and characters from popular video games.” The (proto)fascist male body has been depicted as a machine that is both a tool and weapon since the aftermath of World War I. It’s no coincidence this is around the same period as both the beginning of the armored superhero and villain in illustrated comic books and at the culmination of the disfigured body in the dadaist and surrealist movements. The age of mediated sociality.

Freud belabored that the traumatized soldiers and battle-afflicted populations from war (women, children, etc) marked the return of something dreadful. Particularly, he stressed, it was the return of the repressed. This was a condition of the socially and/or sexually distressed as illustrated by the Dadaist and Surrealist artists. Perhaps, then, the sculpted, aposematic armor of superheroes and villains diagnoses the treatment of the male body as a machine engineered “as a ridiculous weapon and impossible tool,” as the art historian Hal Foster has posited. […]

John Belknap, Kyle Thurman: beyond the night’s philosophy, CFAlive, 2019.

PRESS