“Toilets in modern water closets rise up from the floor like water lilies. The architect does all he can to make the body forget how paltry it is, and to make man ignore what happens to his intestinal wastes after the water from the tank flushes them down the drain. Even though the sewer pipelines reach far into our houses with their tentacles, they are carefully hidden from view, and we are happily ignorant of the invisible Venice of shit underlying our bathrooms, bedrooms, dance halls, and parliaments” – Tereza in The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984) by Milan Kundera (b. 1929)

Sydney Shen is an artist of countless obsessions. Scents, video games, torture devices, gore movies, necropastoral literature, history of epidemics, conceptions of the purgatory, are amongst some of the subjects she manipulates and fields she evolves within; through a practice that comes across as both opulent and deadly: a lethal parade.

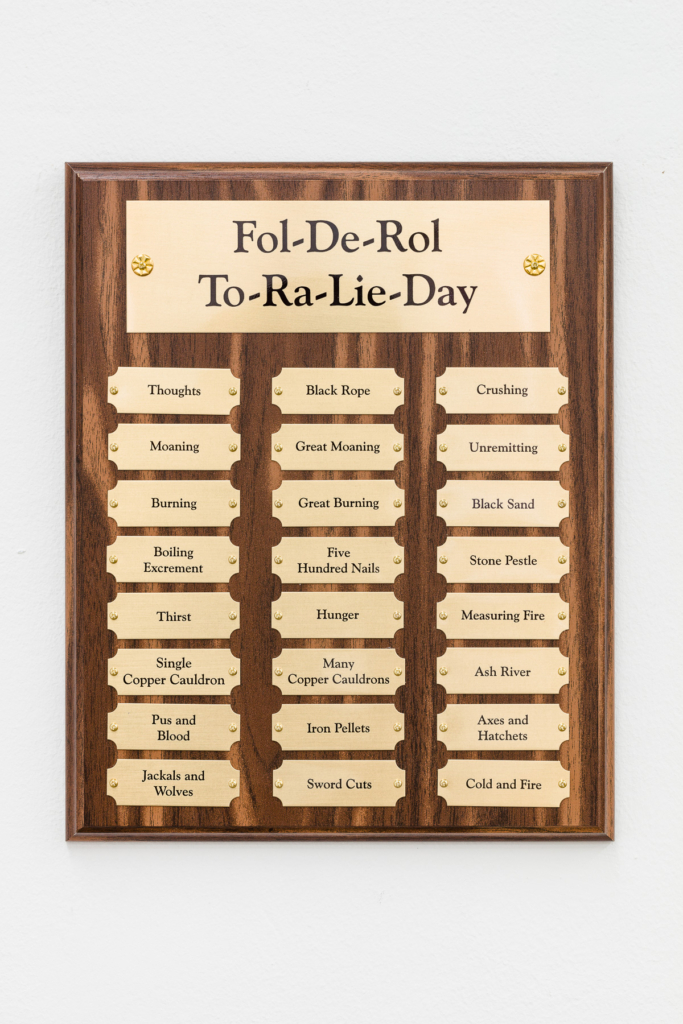

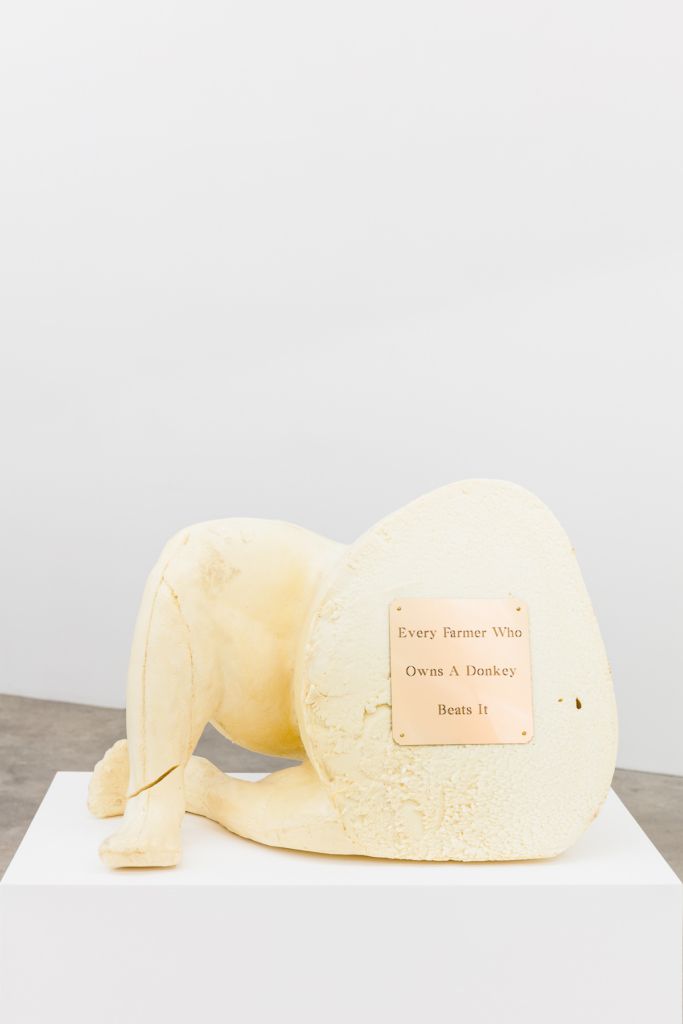

Her latest project, Every Good Boy Does Fine, introduces in Sophie Tappeiner’s spaces an odd display of objects: there, you will mostly find antique wooden children’s training potties (which strangely look like torture instruments), a mechanical animal restraint device (for rabbits and the likes), as well as the foam form of a black bear meant to be used by taxidermists, cut in half, in the position of an odalisque (which could as well be a humanoid demon, if you ask me). That’s in the main space. If you pass the central wall to reach the gallery’s desk space, you will encounter a few more elements: the skeleton of a rabbit popping out of a see-through magician’s hat, and a few nameplates. The latter actually contaminate all of the components of the show: from the sculptures on plinth to the gallery’s desk (“Regulator of the Ultimate Void”). Some even adorn the gallerist and her assistant, and a whole series of them are presented on a wooden mount.

Impudent labels, recalling an utterly bureaucratic world where titles and rewards are everything, they are also playing against their own functions. Where they should help naming, defining and locate, they are, most often than not, tricking you (and me). It would be easy to start listing their different sources and genres: mnemotechnic phrases (like “Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally”), logic problems (such as “Every Farmer Who Owns a Donkey Beats It”), or meme excerpts (refer to “5000 Years of Civilization Reborn”). Some others employ the NATO phonetic alphabet (“Hotel Echo Romeo Oscar”) and the ones in the gallery space’s desk area are borrowed from Asian mythological or proto-mythological origins: the one on the desk to the title of a 14th century Chinese story of the same name (“The Regulator of the Ultimate Void”) and the gathering of nameplates to the different types of torture once can experience at different levels of the Buddhist hell (the access to which is a bureaucratic nightmare in the first place).

However, the master stroke of the artist is not so much to be found in the allocation of the plaques to objects, but much more in their gathering, which ultimately creates a linguistic vertigo: it’s the paroxysmal use of the nonsensical. Wittgenstein would be proud. By giving up on the logic of language as we usually use it, Sydney Shen creates voids in language, which renders its use obsolete. Funny enough, these voids are also physically manifested by the objects in the shows: the toilet devices, the absent top half of the bear form, the fleshless rabbit which could have as well been the victim of the restraint mechanism: all hint at the absent and the void (which, in Chinese, also means fiction), as the outcome of punishment. The plinths themselves, on which the potties sit, are also agents of voids, although full (the multitude suggested by the corn suggests disappearance; and the entry door to one of the plinths, at its bottom, suggest that there are ways to get inside… to find what?).

You might now ask why this Milan Kundera quote as an opening to this piece? The reference feels both obvious and extremely estranged to the exhibition. However, is it not the first time Sydney Shen employs toilets-related appliances in her exhibitions (cf. Urinal / Urine Sample Reed Diffuser Set, 2017 for “Four Thieves Vinegar” at Springsteen Gallery in 2017 or Midnight Game, 2017 for “What’s Worse Than The Void is Matter” at Motel in 2017 as well as her video game Master’s Chambers, produced in 2016 for her solo exhibition of the same name at Interstate Projects). These out-of-date toilets seem to refer to two things to me (which lead to more): a technological history of ablutions as well as a metaphysical narrative of the concept of void in relation to visibility (of body fluids and excrements). Ultimately, in the context of Sydney Shen’s exhibition, it makes me ask: is discipline a form of torture? Is learning how to shit one of the terrestrial torture of hell? Here Kundera starts to make sense. It also does, quickly, recall a specific urinal whose inscription “R.Mutt 1917” wasn’t on a nameplate. How do you (a)void that?

Cédric Fauq