Sabeth Buchmann in conversation with

Anna Schachinger

Sabeth Buchmann In spite of their serial character, the individual pictures seem distinctly individual –

as if one does not result from the other.

Anna Schachinger No.

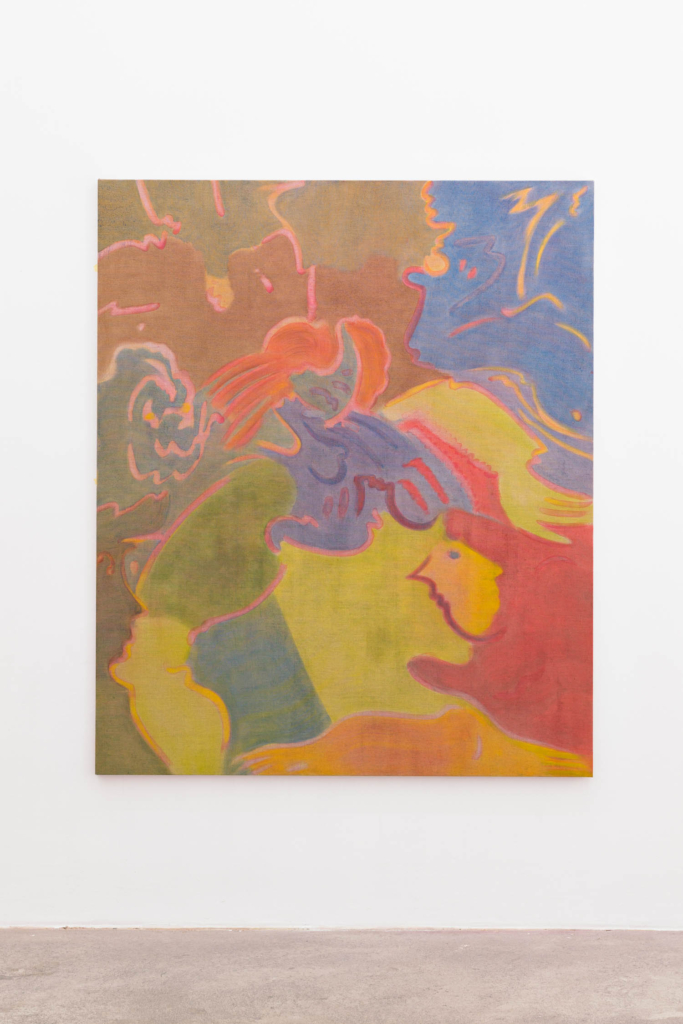

SB That may be a result of their varying colors, but also of the different degrees of implicitness and explicitness of the figurative, which make the pictures readable in different ways.

AS Yes.

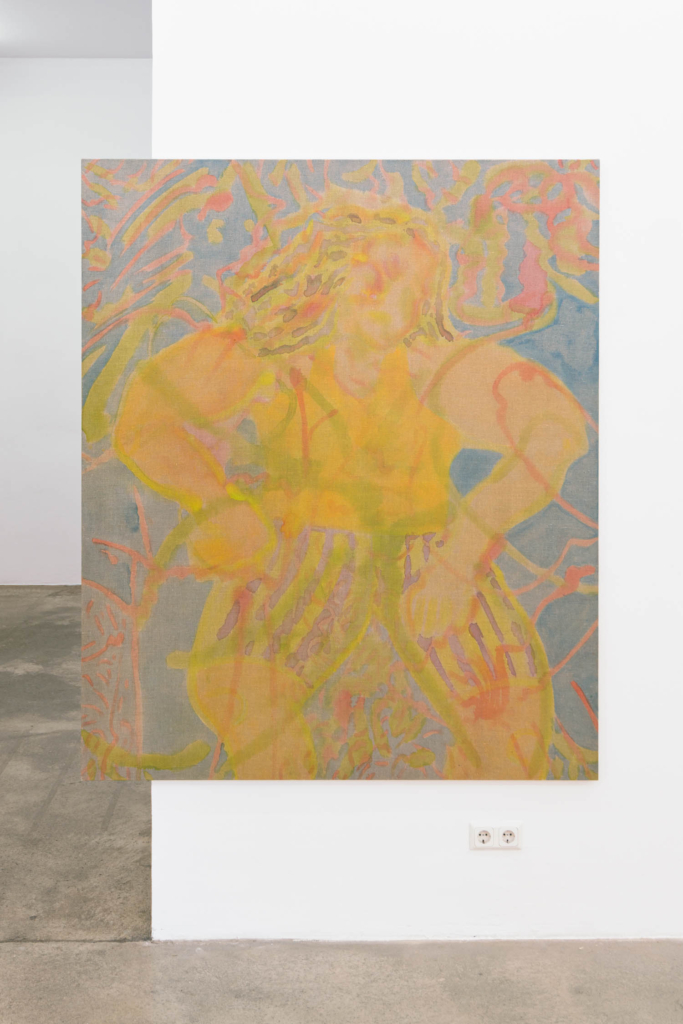

SB Is it fair to say that contrast is a driver for the specific configuration of each painting? True, there are a few basic elements that recur – for example, the ‘allover’ treatment of the surface or the ornamental interweaving of figure and background, which makes some works function more abstractly and others more narratively.

AS Yes, because each painting develops directly on the canvas, it can develop freely, develop in various directions.

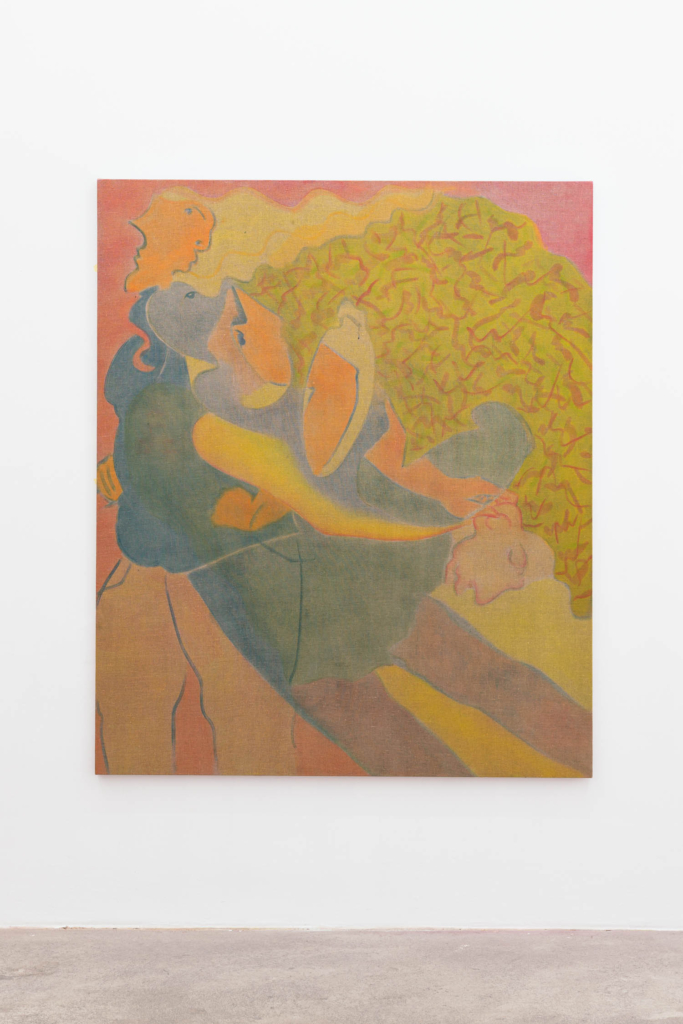

SB The way the depicted body parts meet, the way they are arranged in relation to each other, on the one hand seem to refer to concrete bodies, yet on the other hand construct a body of painting or from painting – a body that oscillates with the surface or the background. Figuration is the structure and vice versa. Where the bodies begin and where they end is not visually discernible.

AS That’s part of the content of these works.

SB How do your paintings develop? I have the impression that you are concerned with the visibility of the painting process – working with in-the-making – that is, that you make visible corrections in the paintings.

AS They are visible decisions against something that was already there. But you can always see what I decided against. For example, here, the heads of these figures were actually down here first, and then I put them up here…

SB Yes, the faces are indeed still visible. I would have seen them as part of the picture, as compositional doubling of motifs, giving the appearance of deliberate pentimenti.

AS Exactly. But that’s precisely why it’s hard for me to call these decisions corrections, because it’s an extension of the narrative and composition of the picture.

SB This also has something conundrum-like in the sense of what I said before: If certain color zones appear as backgrounds at first glance, they turn out to be parts of bodies at second glance. When looking at the pictures, I have to constantly think about which elements belong to which bodies. Limitations turn into immanent relations of form – a moment that also shows itself in the gender of your figures. At the same time, I wonder whether, despite all their hybridity and transition, they are first and foremost conceived in terms of femininity?

AS I would say so. Yes.

SB With regard to the painter Amy Sillman, this leads me to ask about your interest in the open, discontinued forms of Abstract Expressionism. For her part, the American painter tries to take up these forms again qua gendering and thus makes clear that there can be no gender-neutral image.

AS In the history of Western painting representations of femininity are everywhere, but from a very specific point of view. To continue with this, but to take it somewhere else, that’s what interests me.

It’s a famous story that the first abstractions derived from nude drawings of a female body. To then bring that back, to say yes, this is abstract, and it’s intentionally the female body, but the way Amy Sillman wants to express it, and not as a projection surface for the masculine, that I find exciting.

SB So you have a form of femininity in mind that is not traceable to masculinity, one that sets itself as a consciously constructed universality? Is the pale glaze of some of your paintings, possibly produced with the addition of white paint, related to this process of ‘queering’?

AS It’s just painted thinly.

SB That creates the impression of a material-aesthetic minimalism.

AS I think it’s also because I don’t want to keep painting when I feel like everything that needs to be said has been said in a particular painting..

SB Isn’t it also a matter of denaturalizing the color itself and taking away the appearance of substantiality, thereby creating an all the more artificial color effect?

AS Yes. To me, painting is always a stage, always artificial. Especially when it performs naturalism. To me, using only as much color as I need to render a specific idea, is a much more natural approach to the material. But what do you mean by denaturalization?

SB I mean it as a negation of self-evident color matter. In your works, technical levels always resonate, and the color compositions make us question the conditions of their coming into being and their arrangement in the picture.

AS For me, color is also part of the structure, and it is important to me to think about the structures around painting and having them be accessible for the onlooker too. I don’t want the structures to be something that can just disappear, I want the canvas, the paint, and the way the paint is applied to become a part of the work.

SB You previously mentioned your interest in the classical aspects of painting. What exactly is the claim behind that?

AS It’s not a claim at all. I think of it more as a limit.

SB I automatically thought of the formalist credo of medium specificity.

AS Yes.

SB With reference to what you said earlier about your interest in representations of the body, after all, that credo can’t be a neutralist one – so what is your discourse of painting?

AS A queer feminist discourse.

SB The medium as and in the body?

AS Exactly. Yes, and a sense for the body that extends further in and out than its own skin. I’m interested in the question of how bodies influence each other.

SB A simultaneously aesthetic and social body that connects with its surroundings and is dependent on other bodies?

AS Yes, and they even only become bodies through their relationships with others, through their surroundings.

SB While we are talking, we’re looking at your paintings. While doing so, I cannot help but notice that new associations and readings keep coming into play. Suddenly, in what I just identified as a deformed phallus, I now seem to recognize as a parasol… the object as body extension?

AS Exactly, an extension of the tasks of the body… Yes, I’m interested in how to build nonlinear narratives in an image. Through the ambiguous, but also through the circular, where levels of meaning collide, which then allow for contradictions in the image.

Sabeth Buchmann lives and works in Berlin and Vienna, art historian/critic,

professor of modern and post-modern art at the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna; Co-editor of ‘Polypen’ – a series of books on art criticism and political theory; regular contributions to art magazines, catalogs and anthologies. Advisory board member of the journal ‘Texte zur Kunst’; board member of the European Kunsthalle and second managing director of the Austrian Ludwig Foundation. Recent publications: Erprobte Formen oder Kunst als Infrastruktur des Ästhetischen (2022); co-ed. Broken Relations: Infrastructure, Aesthetic, and Critique (2022); co-ed. Putting rehearsals to the test. Practices of Rehearsal in Fine Arts, Film. Theater, Theory, and Politics (2016).

PRESS